Alexie Garcia

Crimson Chronicle Staff

Hearing the phrase “dementia” can elicit a range of emotions. As cases of dementia begin to rise internationally, it becomes clear that there is a lasting impact that spans far beyond just the person suffering, but also to their immediate community.

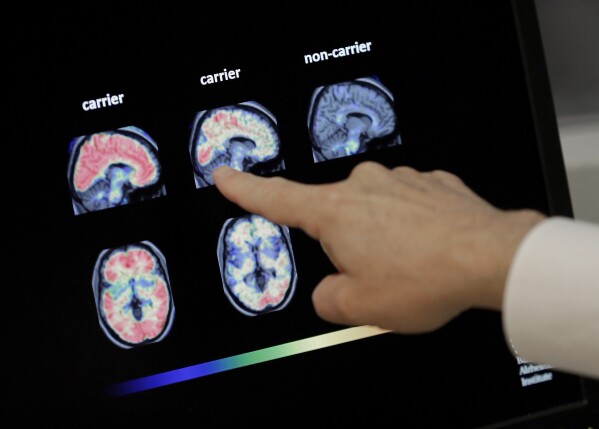

Deriving from the Latin root “demens,” the word essentially translates to “a state of being out of one’s mind.” Dementia itself is an umbrella term for a range of cognitive symptoms that can impede a person’s ability to perform daily tasks. The most common of these symptoms include problems with short-term memory, difficulty completing familiar tasks and changes in mood and personality. These symptoms can arise from a variety of different diseases a person may have, perhaps the most infamous of which being Alzheimer’s disease.

Over a hundred years ago, a German psychiatrist named Alois Alzheimer intensively studied an “unusual disease of the cerebral cortex”, in a female patient named Auguste Deter, who was admitted to the asylum where he worked. Once admitted, she experienced all the stages of deterioration that we now know are caused by Alzheimer’s disease until her ultimate death from sepsis, which her body was no longer able to fight due to Alzheimer’s, at age 56. After her death, Alzheimer studied the structure of her brain and went on to identify the numerous abnormalities leading to her death, which provided much of the framework for present day knowledge on the disease.

Today, there are over 55 million people worldwide living with dementia, killing more people than breast and prostate cancer combined. In the US alone, over 7 million people are currently living with Alzheimer’s–leading the CDC to name it as the seventh leading cause of death in the nation.

These numbers are only expected to grow in the coming years; estimated growth rates predict that, at our current pace, international cases of people living with dementia will double every 20 years. Statistics show that cases are estimated to rise to 78 million in the next five years, and skyrocket to 139 million cases by 2050.

The sheer loss of life would have catastrophic economic, emotional, and physical impacts on communities across the globe. Currently, the cost of dementia (referring to out of pocket care from families, social care in residential homes or by other professionals, and medical bills) is over 1.3 trillion dollars. To put that into perspective, if global dementia was considered its own country, it would rank as the 14th largest economy internationally.

However, despite the universal impact of the disease, cases have been found to disproportionately impact historically marginalized populations. In the United States, Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and Latino’s were the top three most likely racial/ethnic groups to develop dementia. In fact, data shows that non-Hispanic Blacks and Latinos are around twice as likely to have Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in comparison to their non-Hispanic white peers.

This disparity is due to a number of reasons. A lack of accessibility to adequate healthcare and the amount of care received are prominent factors.

From inappropriately funded clinics, closing hospitals, underpaid doctors, and a lack of medical supplies including medicines and clinical drugs, the quality of care given to marginalized groups is significantly less than their higher-income, predominantly white counterparts.

These effects can especially be seen in historically redlined communities across the United States. These communities encounter an increased risk of diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and high blood pressure–all of which contribute to the development of dementia.

Marginalized communities are facing systemic hospital closures, and are also prone to economic struggles and barriers. This results in individuals being forced to work lower paying, but higher demanding jobs that impeded their ability to receive regular medical care due to a lack of time (exacerbated by longer drives to find hospitals that are not closed) and a lack of financial means.

Due to this combination of factors, the age at which people in these circumstances are getting diagnosed with Alzheimer’s is much later in life–and in the progression of the disease. Not only does this mean that the likelihood of slowing down the rate of deterioration is smaller, it also results in significantly higher hospital, physician, and home health service bills.

This affects not only the patient and their struggle with the disease, but the caregivers and immediate family as well. Caring for a loved one with dementia is financially strenuous regardless of the conditions, yet in already economically unstable households, it could perpetuate the cycle of poverty (and thus lack of access to proper healthcare) exponentially.

Even those that are fortunate enough to receive care are more prone to experience barriers in communication with healthcare professionals.

Language barriers are a common example of these difficulties. They often lead to misinterpretation of a patient’s symptoms and the severity of their disease, resulting in inaccurate diagnosis or inappropriate treatment plans. These effects are particularly detrimental to the progression of Alzhimer’s disease, which begins to develop in gradual stages over time. An inability to communicate or recognize the beginning stages of the disease prevents patients from receiving preventive care, thus rates of deterioration are higher and caught at a point where there is a limited ability to delay the process.

This communication barrier also contributes to individuals not seeking care in the first place. Many of those with dementia are on some level aware of the symptoms they are experiencing; yet many are often in denial of what is happening. The experience of seeking help for dementia can induce fear or anxiety that makes a person weary of seeking help as well–further exacerbated by a fear of receiving inadequate care, or not being understood in medical settings.

While fully closing the gap in access to healthcare involves an undoing of centuries of systemic racism, the growing numbers give reason to at least start addressing the issue of increased rates of dementia in marginalized communities.

Encouraging young people from underrepresented populations to pursue education in medical fields is an essential way to reduce disparities in and ensure better quality and access to healthcare. It is professionals who have seen or experienced the direct impacts of historical racism and discrimination on overall wellness who are most likely to advocate for changes from inside the system. These individuals are also the most capable of meaningfully communicating information about prevention and treatment of underdiagnosed diseases such as Alzheimer’s to marginalized communities as well. This is especially important because of the nature of the disease, which causes individuals to need substantially higher levels of support from their doctors and families. Those with dementia are often scared and confused so it is vital that they are able to communicate with their support network in a purposeful and effective way. Doing so gives them a greater chance of slowing down the disease, while also giving medical professionals insight that could be used to further advance research about potential cures/treatments.

By fostering curiosity in and giving opportunities to individuals from diverse backgrounds to advance their careers in healthcare, diverse perspectives will be cultivated, ensuring breakthroughs on ways to best address these ongoing issues. Furthermore, by seeking to educate ourselves and loved ones on symptoms, treatments, and ways to prevent dementia and related diseases, we begin to fight against the systems that have long been in place to set us back. In the end, the fight against Dementia is immense and ongoing- but it can only be effective if everyone, from all communities across the globe, have an equal opportunity to fight.

For further resources and education visit:

- https://www.alz.org/

- https://www.alzheimers.gov/

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-and-dementia

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-caregiving

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-caregiving/getting-help-alzheimers-caregiving

- https://www.alzheimersla.org/

- https://www.cdc.gov/alzheimers-dementia/signs-symptoms/alzheimers.html